Whisky Connoisseur

Arthur J A Bell

The Drink of Kings

Whisky Connoisseur

Arthur J A Bell

The Drink of Kings

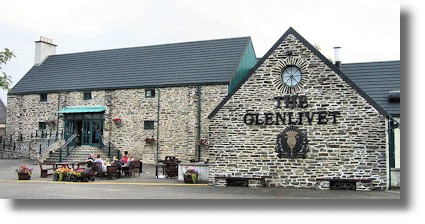

Photo of Glenlivet Distillery via Wikimedia

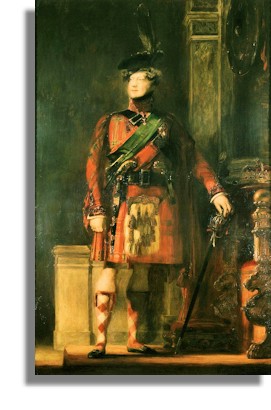

The year is 1822. A mere seven years have passed since Wellington's victory at Waterloo. The British Hanovarian Monarchy has not set foot in Scotland since the 1715 Jacobite uprising attempted to put a Stewart back on the throne. (Graphic on the right is Sir David Wilkie's flattering portrait, painted in 1829, of King George IV in kilt during the visit to Scotland in 1822 with lighting chosen to tone down the brightness of his kilt and his knees shown bare, without the pink tights he wore at the event).The Royal Yacht glides up to the quayside at Kings Landing in Edinburgh's ancient port of Leith, A vast man swaddled in tartan stands on the deck looking at the crowds. Suddenly he spots a "wee kent face" - the great novelist Sir Walter Scott initiator and orchestrater of this historic visit.

The Royal voice booms out: "What! Sir Walter Scott - the man in Scotland whom I most want to see! Let him come up." Thus commanded, Europe's most famed writer goes up the newly lowered gangplank, and presents His Majesty with a silver cross. Then a magic moment. He is invited to share a glass of something completely illegal with King George IV.

The Glenlivet. At cask strength. From Mr. George Smith, a Latin scholar, trained architect, tenant farmer of the Duke of Richmond and Gordon. And a "smuggler"!

Mr Smith's contraband production of the banned uisge-beatha amounted to no more than 50 gallons per week. His Royal Highness would have no other drink at the Royal table In Holyrood Palace.... and one suspects he took a high percentage of the total output. But back to the Shore in Leith ......

Sir Walter asks the king if he could have the honour of keeping the glass which they have just shared. The Royal assent is given, and Scott puts the special vessel in the pocket of his coat.... much later that day, still full of the excitement,he sits down. His biographer son-in-law Lockhart records that Lady Scott heard the most awful scream of "historic pain". She concluded that " he had sat down on a pair of scissors or the like: but very little harm had been done except the breaking of the glass, of which he had alone been thinking." No damage except a punctured posterior,and a consequentially deflated ego!

Now may I "fast forward" you one hundred and fifty one years. To the then family-owned Glenlivet Distillery, high in the Braes above Speyside.I shall return you to the story of Mr Smith and his descendants, but on this day, in the stills designed by the founder, they produced a little bit of history. And I've just managed to get my hands on cask number 4379. This nectar, of the most famous malt in the world, was distilled, and placed in the oak, previously bourbon-used wood barrel,on the 19th of April 1973. What a true pleasure it has been sampling this, for "scientific purposes", naturally.

By coincidence, this was the very week I was setting up my own new Scotland Direct business. As a recent student I had drunk in every one of Edinburgh's pubs (researching for a book, honest!), I had obviously tasted The Glenlivet before then. But little was I to know of the wonders of natural strength malts... matured like this one was to be for over 8,500 days in the same oak, in a cool dark stone and slate bonded warehouse.

This bottling is to supermarket whisky as a third-hand Fiesta is to a new Ferrari. And it's limited to less than 270 numbered bottles... in the whole world. You will remember those blessed angels ... well the cherubim and seraphim enjoyed tippling at cask number 4379 for all of these 8560 days including Sundays!

The tiny quantity I have is equal to the late George Smith's weekly output in Upper Drummin Farm all those years ago. Today the Canadian owners Seagrams produce 320,000 cases a year...that's over 3.8 million bottles.

Now just why is this particular malt so precious?

Well lets go right back to those grim post '45 years. Whisky and tartan were banned. Great swathes of the vast Caledonian forest were being burned or cut down for sheep ( and we go on today about Brazil and the rain forest!) In one year one Speyside landowner sold 60,000 trunks of mature trees to be burned in England's furnaces, whilst another slashed down and burned twelve miles of oak, alder, rowan and Scots pine! (Graphic from Wikimedia shows some surviving Scots pines of the Caledonian fores). The glens were becoming bleak places.... but the illegal distillation of whisky kept the spirits up. In Glenlivet there were over two hundred illicit stills at work, and the courts in Grantown and Keith were busy levying? fines throughout the year. Over 700 convictions are recorded for 1834 alone.Parliament wanted to rectify. - they always do, don't they, in these situations of their own making? The Duke of Gordon piloted the 1823 Excise Act through the Lords, allowing distilling to go on, if the distiller paid a license fee of? Not too popular with the lads! The Duke persuaded the tenant of Upper Drummin, Mr Smith, to take out the first licence, and he thus became deeply unpopular with his neighbours. Indeed so fearful of his distillery being burnt down to the ground "with me in the heart of it", he wrote, that he had to employ armed guards. One of them Captain William Grant married Smith's daughter Margaret, and then opened his own distillery.... but that's another story.

Now long before he spent his, tenner on a licence, the forward-looking George had focused on quality, not firewater. Lady Grant of Rothiemurchus tells us that it was her rather who introduced George IV to the whisky from Mr Smith. She writes: "it is long in wood... mild as milk...and with the real contraband gout in it!"

All this establishment support did not lessen the distiller's fears for the safety of himself, his family, and his distillery Smith recorded "The outlook was an ugly one. The Laird of Aberlour presented me with a pair of hair triggered pistols worth ten guineas, and they were never out of my belt for years."

But things do move on. Young George Gordon Smith, trained as a lawyer, joined his father in the business, and they started expanding the market. When the Speyside Railway was opened in 1863 new markets beckoned. (Graphic by Ronnie Leask, via Wikimedia, shows the old railway station at Aberlour). A new distillery, the one still in use today, had been constructed at Minmore in 1858, and the fame really began to spread. By the time old George (the distiller, not the King), had gone off for his permanent share with the angels, he was a rich man. The tenant farmer, who had turned 300 acres of wild moorland into barley growing pastures, at the end owned 20,000 acres. I suppose it goes to show what you can do with the right? investment.

As the industry grew so did the number of people using the name Glenlivet. George Gordon Smith was a legal eagle, and he took all 18 of them to court and in 1880 he won a partial victory. Their Lordships agreed that only Mr Smith could call his whisky "The Glenlivet", although others could use the name as a suffix.

After his death in 1901, his nephew (remember his sister Margaret?), one Colonel George took over the reigns, passing them on in turn to his son Captain Bill Smith MC. Now he was the bright spark who went to the USA during Prohibition to sell his whisky. Not daft!. Old George would have been proud of his foresight, as the Captain reckoned the absurd ban would be lifted, and he wanted to be in pole-position the minute it was.

The international reputation of this superb whisky just grew and grew, winning gold medals galore. In 1952 they merged with the family owned Glen Grant, and in 1970 with Hill Thompson and Co., makers of the quite superb Longmorn. Finally, one hundred and fifty four years after the Duke persuaded Mr Smith to become the first licenced distillery on Speyside, the family sold its interests to the Ganadian giants, Seagram. The year was 1977.

But the whisky I've just nosed does not come from the Seagram period! It was produced just as Nixon's top aides were resigning over Watergate, and the last Americans were leaving Vietnam. As the lovers of modern art mourned the death of Picasso, so the talented men high on the Braes of Glenlivet produced the whisky we've now bottled. These Highlanders have their priorities right.So what are its very special characteristics, and what did our tasting panel think of it?

The first comment from one was:"My God, this is something to get your teeth into!" Although it is not as powerful at alcohol strength of 54.2% as some we selected previously, it is mellow and unbelievably smooth. It has a distinctive nuttiness on the nose, as well as the palate, and they found it quite full bodied. As they lifted the glasses to their noses they immediately noticed the richness and detected hints of vanilla. These were not so strong as to lose the aromatic floral notes that are so typical of The Glenlivet. However, as it is so rarely available at either this age, or as a cask strength, that one really cannot compare it with the standard 43% bottlings at 12,18 or 21 years. This is a one-off!

In tasting, we discovered a slight sweetness and gentle malting, but this big whisky has a long finish. As we rolled it around our mouths we noticed how clean it was on our palates, and again experienced its smoothness.

This is one whisky I'm going to be careful whom I invite to share a dram. A masterpiece of the distiller's art, it is some of the last whisky ever distilled by the Smith family. I suppose that if His late Majesty George IV and the good Sir Walter were to turn up at my door, I'd invite them in for a malt fit for a king, but as that's not too likely, my secret store is safe under lock in my cellar! But if Scott does appear, I'll need to watch where he puts his glass.

ArthurJ A Bell CBE

Return to Index of articles on Whisky by the Whisky Connoisseur, Arthur J A Bell

Where else would you like to go in Scotland?