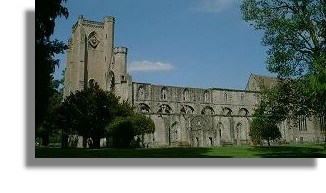

Not surprisingly, the dual imagery ot this Church of Picts and Scots - was also reflected in its organisation. Traces of something like a regional episcopate can perhaps be deduced in parts of the kingdom of the Picts, such as Dunkeld (cathedral pictured here), Brechin and St Andrews as early as the eighth century. But it is no coincidence that the boundaries of these three dioceses were confused and overlapped for they had sprung up around new religious centres. South of the Forth, diocesan boundaries may have been clearer because they corresponded more closely to the secular divisions of the old kingdoms of Strathclyde and Northumbria and were not further complicated by survivals of Columban monasteries. In an organisational sense there may have been by 1000 two churches of the kingdom of the Scots, north and south of the natural barrier of the Forth. But in each there had been a common heritage of Ionan, Pictish and Northumbrian influences; the difference lay in their different proportions.

Not surprisingly, the dual imagery ot this Church of Picts and Scots - was also reflected in its organisation. Traces of something like a regional episcopate can perhaps be deduced in parts of the kingdom of the Picts, such as Dunkeld (cathedral pictured here), Brechin and St Andrews as early as the eighth century. But it is no coincidence that the boundaries of these three dioceses were confused and overlapped for they had sprung up around new religious centres. South of the Forth, diocesan boundaries may have been clearer because they corresponded more closely to the secular divisions of the old kingdoms of Strathclyde and Northumbria and were not further complicated by survivals of Columban monasteries. In an organisational sense there may have been by 1000 two churches of the kingdom of the Scots, north and south of the natural barrier of the Forth. But in each there had been a common heritage of Ionan, Pictish and Northumbrian influences; the difference lay in their different proportions.

It is also too easy to say that episcopacy was on the advance and monasticism was on the retreat. The revival in the Irish Church in the eighth century of the cult of asceticism, a return to the purity of the Columban-type pilgrim, was also felt in Pictland. In the next two centuries, new communities of Céli Dé (servants of God) were established, but they were no longer confined to minor centres such as Loch Leven; they were now also attached to major royal and religious centres such as Kulrimont and Dunkeld. The Culdees, as they are usually called, are the symbol of a Celtic revival in a post-Columban Church, which had survived the dismemberment of the Ionan paruchia. Its bishops, whose authority and jurisdiction were gradually being extended, are a reminder that the links of this Church with Rome were being strengthened at one and the same time.

This was a Church within which 'Roman' bishops and 'Irish' abbots were partners rather than rivals, and sometimes combined in the figure of the same cleric. By 865 the annals refer to an abbots the new or revived centre of Dunkeld who had a Gaelic name, Tuathal son of Artgus, but who was also 'chief bishop of Fortriu'. By 906, it is thought, Constantine II had a bishop who may have been based in St Andrews, called Cellach, and it would be to a monastery there rather than on Iona that this king retired in 943. (Graphic - via Wikimedia - is a carving of St Andrew on a 16 century coat og arms of St Andrews). Cellach and Constantine, however, made their announcement in 906 at Scone and it seems obvious that the authority of these two bishops extended far beyond the narrow bounds either of St Andrews or the old tribal kingdom of Fortriu. The first appearance of a bishop who was denoted by the specific name of his diocese came only in the reign of Alexander I, with Turgot, who was referred to in 1108 as 'Bishop of the Church of St Andrew of Scotland'. And the saying attributed to Giric (878-89), who gave 'freedom to the Scottish Church' was probably not written until about the same period.

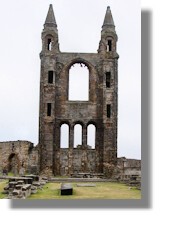

The first explicit recognition of a national 'Scottish Church' came in a papal bull of 1174, which acknowledged its status as a 'special daughter' of Rome. There are, however, many examples in the later tenth and the eleventh centuries of bishops of Kilrimont (later named St Andrews - graphic shows the ruin of St Andrews Cathedral) who were called either 'Bishop of the Scots' or 'High Bishop of Scotland'. Their status was probably akin to that in the Irish Church of bishops resident at Armagh. By then, well before the better-known efforts of Queen Margaret and her sons between 1070 and 1153, the firm foundations of a distinctive, national Church had been laid. A close link between Church and King, the merger of two cults of national saints and a new vision of the duties of Christian kings had all existed since the eighth century. Yet each of these developments had in turn come from the varied experiences of the different early kingdoms which made up the later composite kingdom of the Scots. The ninth- and tenth-century Church lay at ease with its past. In this, the church of a confederate people, Roman and Celtic traditions, abbot and bishop co-existed, as did the cults of Columba and Andrew, Adomnán and Ninian.

Not surprisingly, the dual imagery ot this Church of Picts and Scots - was also reflected in its organisation. Traces of something like a regional episcopate can perhaps be deduced in parts of the kingdom of the Picts, such as Dunkeld (cathedral pictured here), Brechin and St Andrews as early as the eighth century. But it is no coincidence that the boundaries of these three dioceses were confused and overlapped for they had sprung up around new religious centres. South of the Forth, diocesan boundaries may have been clearer because they corresponded more closely to the secular divisions of the old kingdoms of Strathclyde and Northumbria and were not further complicated by survivals of Columban monasteries. In an organisational sense there may have been by 1000 two churches of the kingdom of the Scots, north and south of the natural barrier of the Forth. But in each there had been a common heritage of Ionan, Pictish and Northumbrian influences; the difference lay in their different proportions.