Scots History to 1400

By Michael Lynch

This is a section from the book "Scotland: a New History" by Michael Lynch which covers Scottish history from the earliest times to the present. There is an Index page of all the sections of the book up to the end of the 14th century which have been added to Rampant Scotland. The pages were previously part of the "Scottish Radiance" Web site.

Saints and Saints' Cults

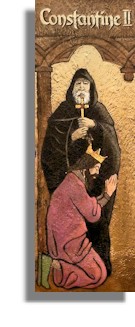

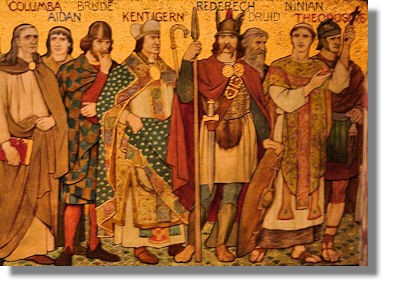

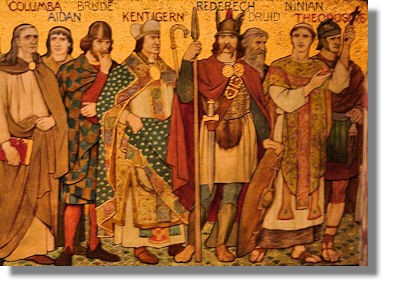

Saints Ninian, Kentigern, Aidan and Columba, National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh

Saints are not born, they are created. More powerful in death than in life, they become, once acclaimed, the servant of future generations of the servants of Christ. Ninian (see graphic on right), Columba, Adomnan (the most important but not the first of Columba's hagiographers), and Kentigern, probably the four best-known early Scottish saints, all became subjects of a cult within a few decades of their deaths, but they were all also later recast, often as late as the twelfth or thirteenth centuries, as born-again saints to fit new fashions of hagiography or the demands of contemporary ecclesiastical politics. Our information about them and other early apostles of Scotland is entangled with the assumptions and motives of many generations of biographers and hagiographers. Medieval Scottish chroniclers were intent on tracing the long genealogy of present kings to demonstrate their status. Medieval chroniclers of the early Church were concerned with subsuming the long, difficult and doubtless uneven story of the progress of Christianity into a cult of the personality of a few holy men, at the expense of the trials of successive generations of missionaries whose role remains obscure and unsung.

Saints are not born, they are created. More powerful in death than in life, they become, once acclaimed, the servant of future generations of the servants of Christ. Ninian (see graphic on right), Columba, Adomnan (the most important but not the first of Columba's hagiographers), and Kentigern, probably the four best-known early Scottish saints, all became subjects of a cult within a few decades of their deaths, but they were all also later recast, often as late as the twelfth or thirteenth centuries, as born-again saints to fit new fashions of hagiography or the demands of contemporary ecclesiastical politics. Our information about them and other early apostles of Scotland is entangled with the assumptions and motives of many generations of biographers and hagiographers. Medieval Scottish chroniclers were intent on tracing the long genealogy of present kings to demonstrate their status. Medieval chroniclers of the early Church were concerned with subsuming the long, difficult and doubtless uneven story of the progress of Christianity into a cult of the personality of a few holy men, at the expense of the trials of successive generations of missionaries whose role remains obscure and unsung.

Unpicking the story of Scottish Christianity is as much a task of stripping off the layers of camouflage put in place by hagiographers as it is a search for clues beyond the few hard facts that exist. Much turns on the interpretation of laconic, sometimes one-line pronouncements which have often been made the headlines of the story of early Christianity. Bede (picture on the left via Wikimedia) wrote of Ninian only in an aside to his fuller story of Columba's mission to convert the northern Picts: 'the southern Picts who live on this side of the mountains had, it is said, long ago given up the error of idolatry and received the true faith through the preaching of the Word by that reverend and saintly man, Bishop Nynia'. But who said this? Bede may have been the first of many historians to conflate Ninian and the Ninianic mission, a saint and his cult. More laconic still is the 'letter' sent by Patrick to Coroticus, King of Strathclyde, criticising him for invading Ireland and enslaving some of Patrick's own converts with his war band of 'mercenaries, heathen Scots and apostate Picts'.

Unpicking the story of Scottish Christianity is as much a task of stripping off the layers of camouflage put in place by hagiographers as it is a search for clues beyond the few hard facts that exist. Much turns on the interpretation of laconic, sometimes one-line pronouncements which have often been made the headlines of the story of early Christianity. Bede (picture on the left via Wikimedia) wrote of Ninian only in an aside to his fuller story of Columba's mission to convert the northern Picts: 'the southern Picts who live on this side of the mountains had, it is said, long ago given up the error of idolatry and received the true faith through the preaching of the Word by that reverend and saintly man, Bishop Nynia'. But who said this? Bede may have been the first of many historians to conflate Ninian and the Ninianic mission, a saint and his cult. More laconic still is the 'letter' sent by Patrick to Coroticus, King of Strathclyde, criticising him for invading Ireland and enslaving some of Patrick's own converts with his war band of 'mercenaries, heathen Scots and apostate Picts'.  If Patrick (that's St patrick's Cathedral, Dublin on the right, via Wikimedia) was so scathing because this was an act of treachery rather than another act of violence, the spiritual treachery of recent converts who by the 470s had deserted the faith, who had converted these 'Picts' but Ninian? But if this was so, it may show how fragile conversion was in the first Christian centuries, even by a charismatic leader such as Ninian. Early evangelisation, which depended so much on a conversion of the senses rather than the intellect, on the magic of miracles and prophecies rather than the preaching of the faith, could be countered by a greater magician or by the failure of its own magic, when crops failed, women turned barren or battles were lost. There was no tidal wave of Christianity sweeping across a hostile and difficult terrain, nor should we expect one.

If Patrick (that's St patrick's Cathedral, Dublin on the right, via Wikimedia) was so scathing because this was an act of treachery rather than another act of violence, the spiritual treachery of recent converts who by the 470s had deserted the faith, who had converted these 'Picts' but Ninian? But if this was so, it may show how fragile conversion was in the first Christian centuries, even by a charismatic leader such as Ninian. Early evangelisation, which depended so much on a conversion of the senses rather than the intellect, on the magic of miracles and prophecies rather than the preaching of the faith, could be countered by a greater magician or by the failure of its own magic, when crops failed, women turned barren or battles were lost. There was no tidal wave of Christianity sweeping across a hostile and difficult terrain, nor should we expect one.

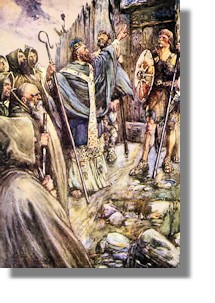

Bede, by contrast, saw Columba not only as 'apostle of the Picts' beyond the mountains of the Mounth but also as the key link with the church of his own day: his 'monasteries placed within the boundaries of both peoples [Picts and Scots] are down to the present time held in great honour by them both'. (Graphic, via Wikimedia, shows Columba at the fort of the Pictish King Bridei). The historic abbot, the cult of Colum Cille and the expanding of paruchia or monastic family of Iona not distinguished from each other. It would have been surprising if they had been for since the time of Columba the work of some seven generations of abbots, who were. literally his 'heirs' (which is the meaning of the usual Irish word for abbot, comarba), had been to advance the reputation of a growing and eternal spiritual family, of monks and monasteries. Yet how did Columba, a kinsman of an Irish royal family, whose efforts in his own lifetime were narrowly concentrated along the western seaboard of Scotland, from Loch Awe in the south to Skye in the north, and who was thus a saint not even of Dalriada but of the CenÚl Loairn whose territory this mostly was, come to be acknowledged as a saint of the confederation of peoples which would come to be encompassed in the kingdom of the Scots?

Bede, by contrast, saw Columba not only as 'apostle of the Picts' beyond the mountains of the Mounth but also as the key link with the church of his own day: his 'monasteries placed within the boundaries of both peoples [Picts and Scots] are down to the present time held in great honour by them both'. (Graphic, via Wikimedia, shows Columba at the fort of the Pictish King Bridei). The historic abbot, the cult of Colum Cille and the expanding of paruchia or monastic family of Iona not distinguished from each other. It would have been surprising if they had been for since the time of Columba the work of some seven generations of abbots, who were. literally his 'heirs' (which is the meaning of the usual Irish word for abbot, comarba), had been to advance the reputation of a growing and eternal spiritual family, of monks and monasteries. Yet how did Columba, a kinsman of an Irish royal family, whose efforts in his own lifetime were narrowly concentrated along the western seaboard of Scotland, from Loch Awe in the south to Skye in the north, and who was thus a saint not even of Dalriada but of the CenÚl Loairn whose territory this mostly was, come to be acknowledged as a saint of the confederation of peoples which would come to be encompassed in the kingdom of the Scots?

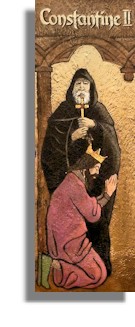

The story of the consolidation of Christianity under the mac Alpin kings is almost as mysterious as that of its beginnings. When Giric succeeded c. 878 a note in a much later Latin king list says that he 'was the first to give liberty to the Scottish Church, which was in servitude up to that time after the custom and fashion of the Picts'. This may mean that the rights of lay proprietors were abolished, in acute anticipation of the settlement of the tithe on parish churches in the reign of David I, some 250 years later, or it may simply mean that a Church, like a people in a time of the assimilation of cultures, laws and customs, expected to have its privileges acknowledged and confirmed by kings. In 906, Constantine II and his bishop Cellach climbed the 'hill of Faith' near Scone to proclaim that 'the rights in churches and gospels should be kept in conformity with [the customs of] the Scots'. The secular equivalent of the pronouncements of Giric and Constantine may have been the promulgation of the mysterious leges Kenneth Macalpinae, another guarantee of continuity with the past rather than a harbinger of change. But this can only be speculation, as is so much else. In a sense, the first 500 years of the story of Scottish Christianity begin and end with a conundrum.

Saints are not born, they are created. More powerful in death than in life, they become, once acclaimed, the servant of future generations of the servants of Christ. Ninian (see graphic on right), Columba, Adomnan (the most important but not the first of Columba's hagiographers), and Kentigern, probably the four best-known early Scottish saints, all became subjects of a cult within a few decades of their deaths, but they were all also later recast, often as late as the twelfth or thirteenth centuries, as born-again saints to fit new fashions of hagiography or the demands of contemporary ecclesiastical politics. Our information about them and other early apostles of Scotland is entangled with the assumptions and motives of many generations of biographers and hagiographers. Medieval Scottish chroniclers were intent on tracing the long genealogy of present kings to demonstrate their status. Medieval chroniclers of the early Church were concerned with subsuming the long, difficult and doubtless uneven story of the progress of Christianity into a cult of the personality of a few holy men, at the expense of the trials of successive generations of missionaries whose role remains obscure and unsung.

Unpicking the story of Scottish Christianity is as much a task of stripping off the layers of camouflage put in place by hagiographers as it is a search for clues beyond the few hard facts that exist. Much turns on the interpretation of laconic, sometimes one-line pronouncements which have often been made the headlines of the story of early Christianity. Bede (picture on the left via Wikimedia) wrote of Ninian only in an aside to his fuller story of Columba's mission to convert the northern Picts: 'the southern Picts who live on this side of the mountains had, it is said, long ago given up the error of idolatry and received the true faith through the preaching of the Word by that reverend and saintly man, Bishop Nynia'. But who said this? Bede may have been the first of many historians to conflate Ninian and the Ninianic mission, a saint and his cult. More laconic still is the 'letter' sent by Patrick to Coroticus, King of Strathclyde, criticising him for invading Ireland and enslaving some of Patrick's own converts with his war band of 'mercenaries, heathen Scots and apostate Picts'.

If Patrick (that's St patrick's Cathedral, Dublin on the right, via Wikimedia) was so scathing because this was an act of treachery rather than another act of violence, the spiritual treachery of recent converts who by the 470s had deserted the faith, who had converted these 'Picts' but Ninian? But if this was so, it may show how fragile conversion was in the first Christian centuries, even by a charismatic leader such as Ninian. Early evangelisation, which depended so much on a conversion of the senses rather than the intellect, on the magic of miracles and prophecies rather than the preaching of the faith, could be countered by a greater magician or by the failure of its own magic, when crops failed, women turned barren or battles were lost. There was no tidal wave of Christianity sweeping across a hostile and difficult terrain, nor should we expect one.

Bede, by contrast, saw Columba not only as 'apostle of the Picts' beyond the mountains of the Mounth but also as the key link with the church of his own day: his 'monasteries placed within the boundaries of both peoples [Picts and Scots] are down to the present time held in great honour by them both'. (Graphic, via Wikimedia, shows Columba at the fort of the Pictish King Bridei). The historic abbot, the cult of Colum Cille and the expanding of paruchia or monastic family of Iona not distinguished from each other. It would have been surprising if they had been for since the time of Columba the work of some seven generations of abbots, who were. literally his 'heirs' (which is the meaning of the usual Irish word for abbot, comarba), had been to advance the reputation of a growing and eternal spiritual family, of monks and monasteries. Yet how did Columba, a kinsman of an Irish royal family, whose efforts in his own lifetime were narrowly concentrated along the western seaboard of Scotland, from Loch Awe in the south to Skye in the north, and who was thus a saint not even of Dalriada but of the CenÚl Loairn whose territory this mostly was, come to be acknowledged as a saint of the confederation of peoples which would come to be encompassed in the kingdom of the Scots?