Scots History to 1400

By Michael Lynch

This is a section from the book "Scotland: a New History" by Michael Lynch which covers Scottish history from the earliest times to the present. There is an Index page of all the sections of the book up to the end of the 14th century which have been added to Rampant Scotland. The pages were previously part of the "Scottish Radiance" Web site.

Pictish Kings -The making of a kingdom

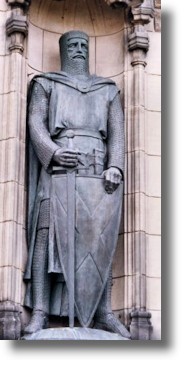

The early history of Scotland is seen conventionally as the story of progress towards the 'making of a kingdom', with the decisive steps being taken in the ninth, tenth and eleventh centuries. But the story was longer than this and it was a two-stage process. The first stage had begun by the end of the third century with the confederation of a number of loosely related tribes under a common name; by the sixth century they were grouped under two overkings and by c. 700 under one overking. The second stage, which belongs largely to the ninth century, was the consolidation of these peoples during a number of key, lengthy reigns which remain amongst the most obscure in the whole of Scottish history. Later chroniclers of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries would focus their attention on the reign of Kenneth mac Alpin (843-58) as marking the end of centuries of Pictish rule and the beginning of a new dynasty. Yet it makes much more sense to think of a crucial century and a half in which fluctuation and consolidation in the Pictish kingdom went hand in hand. What was happening was what historians of a later period might call a clash of continuity and change; such clashes should not be reserved for seemingly decisive reigns, such as those of David I or James VI - or Kenneth mac Alpin (pictured here). It is likely that such a clash marked the whole period between the reign of Constantine, son of Fergus (789-820) and Constantine 11(900-43). Viewed in this way the decisive ninth century turns less on the single, fairly brief reign of Kenneth mac Alpin. Perhaps, rather, we should think of a 'long' ninth century belonging to a trio of kings called Constantine.

The mechanics of these processes were complicated and thinking of them in modem terms, of power bloc politics, brings confusion and contradiction to the problem rather than light. It can be argued that the reign of Óengus I, who emerged in 729 as victor in a power struggle after the retiral of Nechtan, marked the beginning of a Pictish take-over of Dalriada; in 736 he himself captured the fortress of Dunadd in the territory of Cenél nGabráin and his brother, Talorcán, routed a Dalriada army a few miles away, at Loch Awe. Yet, even if Óengus won by conquest the overlordship of Dalriada in 741, by 750 he is said in the Annals of Ulster to have lost it, perhaps because of the intervention of Teudubr, King of Strathclyde. By 768 it was a Dalriadic king, Áed Find, who was invading the Pictish heartland of Fortriu, though with what result is unknown.

The crucial eighth and ninth centuries need to be viewed as a three-dimensional picture. There was recurrent jostling for power on the frontiers of neighbouring kingdoms; except where natural physical barriers reinforced them, frontiers were not fixed and in such circumstances migration across them was as natural an instinct as cattle raiding. There was calculated destabilisation of one kingdom by another or the creation of satellite states. But the status of such client kingdoms might range from the simple paying of tribute to outright overlordship. And there was also considerable cultural cross-fertilisation between peoples, whether produced by intermarriage, changing dedications of saints, or the efforts of holy men.

The result is a confusing one, not to be explained adequately by a history of coup and counter-coup. The King of Picts whom the Dalriadic king, Áed Find, fought in 768 was called Ciniod or Kenneth, son of Dérile; but that was a Gaelic name, as was that of the Pictish king, Óengus son of Fergus who had devastated Dalriada in the 730s. Both Ciniod and Óengus I almost certainly had at least some blood of the Scots of Dalriada in their veins. The evidence for a successful Pictish assault on Dalriada in the mid-eighth century and for a Dalriadic take-over of Pictland in the mid-ninth century can be assembled, but it is more useful to think of two kingdoms coming more closely together in a process which was often acrimonious and on several occasions hostile. These were the quarrels of an extended family, and all the more bad-tempered as a result.

The century before the 840s saw these important processes at work. They depended, however, on a new set of political circumstances, most important of which was the sharp decline in the influence of the kingdom of Northumbria(see map of Northumbria in 802AD). For some, that decline can be seen to have begun as a direct result of the defeat of the Northumbrians at Nechtansmere, which put to an end the short-lived career of Bishop Trumwine and the see of Abercorn, to which he had been appointed only four years before, in 681. Yet set-piece battles, if such Nechtansmere was, seldom mark great turning-points. The reign of Nechtan, which began barely thirty years later, had seen the revival of Northumbrian pressure, spearheaded by issues involving the Pictish Church. But Northumbrian violence was as much a weapon as the gentler overtures of Bede and his abbey of Monkwearmouth and Jarrow; the Picts had been heavily defeated by the Northumbrians on the plain of Manaw, probably somewhere in West Lothian, in 711. The period of the writing of Bede's Ecclesiastical History was, however, a high-water mark of Northumbrian power. The end of Nechtan's reign coincided with the beginning of a century or more of steady decline of Northumbrian influence, not only north of the Forth but also in Lothian and the south-east. That steady but obscure slippage in Northumbrian control over its northern frontier was stemmed briefly by Anglian incursions, supported by the Picts, into Strathclyde in 750 and 756 resulting in the adding of the plain of Cyil (or Kyle) and the winning of tribute from the King of Strathclyde in 756. It is difficult, however, to trace Northumbrian influence between that point and the fall of York in the face of Danish attack in 866.

If the eighth century saw the withering of the influence of Pictland's southern neighbour, it may also have seen a new, closer relationship with another, the British kingdom of Strathclyde. For, as we have seen, the Pictish king victorious at Nechtansmere was Bridei mac Bile, who may have had a father who was a Strathclyde Briton. Nechtan, King of Picts between c.600 and 630, may also perhaps have been, it has been argued, a former King of Strathclyde called Neithon before he became overking of the Picts. The power of kings, whether of the Picts or of other peoples, depended as much on their relationships with their neighbours as on the internal strength of their rule. Status and others' perceptions of it were the key to the authority of early kings. The essential contrast between the two periods, of Northumbrian and British influence, is that much is known and perhaps too much made of the first - both by Pictish historians eager to make Nechtansmere the great turning-point it never was and by devotees of Bede who may give the reign of Nechtan a greater centrality than it deserves - and too little is known of the second. The story of the increasing merging of the Scots of Dalriada and the Picts thus, of necessity, has to be told without reference to the impact made on their relations by their mutually closest neighbour, the kingdom of Strathclyde. Here was not a marriage of two peoples, but a ménage à trois, by its nature more complicated and volatile. We can only guess at its intricacies.

There were two sets of processes at work in relations between Dalriada and Pictland. One had been going on for centuries, the Celticisation of parts of the far flung kingdom of the Picts. A Celtic aristocracy has been detected amongst the Caledonians as early as the first or second centuries; these were a warrior élite who must have held in subjugation a native, non-Celtic peasantry. The name of the minor kingdom of Gowne, if it can be associated with Gabráin, father of Aedán, is an indicator in the sixth century of Dalriadic influence in a part of the kingdom of the Picts well to the east of Fortriu. And both a son and two great-grandsons of Aedán may have become kings of Picts in the late sixth century. These points may all be contentious in themselves, but the emergence of the kingdom of Atholl ('new Ireland') by 739 clearly indicates the presence over a long period of time of new settlers from the west. With Celticisation came intermarriage. There was nothing new about intermarriage between Scots and Picts in the ninth century, nor was it unique. There had, it is likely, long been a similar pattern of intermarriage between Picts and Britons. Two seventh-century Pictish kings - Bridei and Nechtan - were probably linked, as we have seen, to the kingdom of Strathclyde.

The second, parallel process was an almost inevitable consequence of the first: intermarriage between one major dynasty and another or even between the families of minor kings brought about a steady widening of the derbfine. It also increased the likelihood of family squabbles which might lead to tension or violence, either on the frontier or at court. The political purpose of kings of the Picts was clear enough, for by the seventh century they had largely achieved by these means a modus vivendi with their three main neighbours. It is not surprising that by early in the ninth century examples begin to proliferate of kings of Picts who held or had held other kingdoms. More significantly, in the two sons of Fergus, Constantine and Óengus II who ruled between 789 and 820 and between 820 and 834, are to be found the first examples of simultaneous dual kingship of Picts and Scots. Constantine, King of Picts since 789, also became King of Dalriada in 811. His brother, Óengus, who seems to have succeeded him on his death in 820, left as his successor his son, Eóganán, who succeeded to both kingdoms after a short interval during which the two kingships were not combined. Significantly, both Constantine and Óengus were described in the Annals of Ulster at their deaths as 'King of Fortriu'. And in 839 Eóganán met his death leading the 'men of Fortriu' in battle against the Norsemen. Although Skene in his Celtic Scotland argued that the end of the house of Fortriu came in 889, with the death of Giric, who had succeeded the two sons of Kenneth mac Alpin, the date 839 is a more significant one. In 877, when Eochaid, a grandson of Kenneth, disputed the succession, the struggle for the kingship was, as it had often been before, a family quarrel, between the immediate heirs of Kenneth and his brother, Donald I. Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.

The difference between the two periods before and after the mid-ninth century lay not so much in the impact made by a new kind of king, in the person of Kenneth mac Alpin, but in the after-effects of the shattering defeat in 839 when not only Eóganán fell, but also his brother, Bran, 'and others almost without number'. Amongst them, almost certainly, were other prominent members of the derbfine. That defeat ranks amongst the most significant in Scottish history, far more serious than that at Flodden, for here as well as a culling of the major families of the kingdom was effected a decisive shift in the pattern of succession. It was, as we shall see, not quite the beginning of a new dynasty, that of the mac Alpin kings, but it was the effective end of the dynasty of Fortriu, which had ruled with increasing authority since the reign of Bridei, son of Bile, who had been the first to be called 'King of Fortriu' at his death in 692.

The long line of kings of Fortriu deserves a greater place in the process of the making of the Scottish kingdom. By 729 they had clearly been acknowledged as overkings of all the Picts. They left behind them a distinctive and close relationship between King and Church which would lay the foundations for the sons of Malcolm and Margaret in the early twelfth century. They also, probably early in the eighth century, had constructed a mythology of their own past. Frankish kings at about the same date had invented for themselves a Trojan origin; Pictish kings were presented with an equally satisfying Irish one, in the figure of Cruithne, who ruled for no less than fifty years as a 'merciful judge'. By the end of the eighth century, they had also found, in the figure of Constantine, a renewed mythology of kingship which exactly paralleled the revival elsewhere in western Europe in the second half of the eighth century of the idea of a reborn Christian Roman empire of Constantine under a new, more prestigious kind of king. The same process in Gaul would eventually produce a new-style King of Franks, Charles the Great or Charlemagne. In the Pictish kingdom, it produced a series of kings called Constantine, each more closely attached to the Church which cultivated him than the last. The cult of Constantine neatly complemented the cult of St Peter which had been promoted at the Pictish court since the reign of Nechtan, earlier in the same century. Pictish kingship and the Pictish Church, both in a state of slow but profound change in the eighth and ninth centuries, were nourished by each other. It is no accident that the office of 'chief bishop of Fortriu' emerged by 865, in the reign of Constantine I.

But the Constantine who succeeded as King of Picts in 789 was a son of Fergus and elder brother of an Óengus, both obviously Gaelic names. That deliberate choice of names, Constantine and Óengus, made for prospective Pictish kings is as good an example as any, not only of the integrated nature of Pictish society, but also of the wider vision and ambition of the house of Fortriu. A balance was in process of being struck between old and new, between a revived native culture with disparate roots and the importation of a consciously novel western European cult of kingship. Much the same balance between old and new would be struck again, three centuries later, in the reign of David I. The clash of continuity and change lay at the heart of the history of Pictish kingship, fully a century before the reign of Kenneth mac Alpin. By the reign of the first Constantine (789-82O), the process of confederation had brought the peoples of the north to the point where the process of political consolidation might begin. The genres of Picts and Scots had been coming together for a century or more into one people, even if it was, inevitably, a loose confederation. The next stage was for regnum and gens to come together.

Return to Index of Scots History to 1400