Scots History to 1400

By Michael Lynch

This is a section from the book "Scotland: a New History" by Michael Lynch which covers Scottish history from the earliest times to the present. There is an Index page of all the sections of the book up to the end of the 14th century which have been added to Rampant Scotland. The pages were previously part of the "Scottish Radiance" Web site.

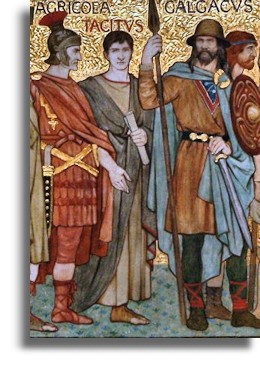

The Land and its People Before AD 400

The records of much of early Scottish history are not written. They lie rather in the standing stones, the brochs and forts which that guarded most of its western and northern coastline, and which were the very sites of royal or ecclesiastical centres, or in the terrain itself. There is little written between Adomnán's Life of Columba composed in the seventh century and Tacitus's account of Agricola's last Roman campaign at Mons Graupius in the early autumn of AD 83, which provides us with the first recorded battle in Scottish history - at Mons Graupius in the early autumn of AD 83. That account is of the relentless pursuit made by the Roman governor of Britain across the Forth and Tay of native tribes led by a chieftain called Calgacus ('the swordsman'). This battle eventually inflicting reportedly huge casualties of 10,000 dead against Roman losses of 360, and bears the unmistakable ring of the excesses of military memoirs. More than a dozen possible sites have been suggested for the location of Mons Graupius, including the Pass of Grange near Keith and Durno, under the lee of Bennachie near Inverurie in eastern Aberdeenshire. Perhaps The most plausible location is perhaps a site south of the Mounth, where the Bernie Water flows below Knock Hill near Monboddo, in the Mearns, a district known in the tenth century as 'the Swordland'. [The Mounth is the range of hills on the southern edge of Strathdee in northeast Scotland. It usually referred to as "the Mounth". The name is a corruption of the Scottish Gaelic monadh - Editor] The importance of this battle is as elusive as its location. Although the tribesmen suffered heavy casualties, it is clear from Tacitus's own account that most escaped into the safety of the nearby hills to fight another day.

The physical evidence found in fort, duns and brochs provides a tantalizing glimpse of what lay further back in Scotland's very early history. It is clear that huge sites such as the one at Traprain Law (picture here by James Denham via Wikimedia), near Dunbar in East Lothian, represented a native hill fort which must have flourished during the period of intermittent Roman occupation of the area to the south of the Forth between AD 78 and 215. Here, on a site 784 feet high which overlooked much of Lothian, there likely was, it is likely, a settlement which had a much older provenance, dating back perhaps to the beginning of the first millennium BC.

In complete contrast, a recently discovered Roman site was at Newstead where Dere Street crossed the River Tweed near Melrose. Called Trimontium (graphic on the right is by Eileen Henderson, via Wikimedia), it was the military equivalent of a new town, a recently rediscovered archaeological site which is now thought to have been not just a temporary fort but a Roman supply camp and industrial centre where iron weapons, armour and tools were made and repaired. And craftsmen fashioned small objects in bronze and lead, roof tiles and pottery vessels.Different again was the fort at Inveresk, near Musselburgh, built early in the Antonine period, probably about AD 140. Although it sits atop a steep slope surrounded on three sides by a river, there was a thriving and substantial civilian settlement (vicus) outside it, on its eastern side. The different kinds of Roman sites suggest a sophisticated system of communications and services for commercial operations as well as careful surveying of the military problems posed by the terrain of northern Britain.

The fort at Inveresk looked towards the dramatic Din Eidyn, the same volcanic rock on which Edinburgh Castle now stands, is barely five miles to the west. Here was the centre of the Gododdin court of the North British king, Mynyddog, c.600. During the period of the first Roman invasions, Inveresk lay within the territory of the Votadini, precursors of the Gododdin. Despite Inveresk’s apparent strategic importance, which would be capitalised upon by kings of Scots and English invaders alike from after the thirteenth century onwards, there is no evidence that the Romans ever occupied it.

Greater and potentially more important than all of these forts above in the early centuries AD was the enigmatic Tap o' Noth, near Rhynie in Strathbogie. The graphic of this location (on the left) is by Alan Findlay via Wikimedia with the fort on top of the rise to the left of the main hill. Here, on a summit over 1,800 feet high, lay a fort of some fifty acres in area. There is clear evidence of at least 200 timber roundhouses, making Tap o’ North four times the size of any other fort in the northeast. Its origins are likely to go back at least as far as those of Traprain Law of Din Eidyn, but its precise status remains a mystery. If a physical site is a guide to the politics of the tribes whom the Romans encountered, this Tap o’ North may have been one of the tribes' keys gathering points. Agricola's expedition of AD 83, even if it reached Strathspey, came no nearer than ten or fifteen miles of this fort.If the huge natural fortified symbol of Tap o' Noth represents the political grouping or confederation of the tribes north of the Forth/Clyde line - probably in reaction against the Roman threat - the different chains of place-names, standing stones, or smaller forts and brochs may be taken as a measure of the extent of their influence or territory. The 'quaking ground of place-names' trembles nowhere so alarmingly as in the tracing of Pictish influence, for the 300 or more 'pet' or 'pit' Pict names, which can be traced, are likely to refer only to good arable or pastoral land. Their (the names or the land?) distribution would limit Pictish influence to the eastern coast from the Black Isle to the line of the Firth of Forth, and infiltrating inland and westwards for only a way along the straths of the Spey, Dee, Don, Tay and Earn. As for the distribution of Pictish monuments, it is more complicated for they are divided conventionally into three classes. However, their overall distribution pattern is much the same as that for 'pit'. (This brief observation is tantalizing, and either needs amplifying, or explained concisely or eliminated).

For contemporaries, however, the most recognisable points of location were fortified places. The Ulster Chronicle in its account of the century after 638 refers to no fewer than twenty-four forts or strongholds, with perhaps ten more which that are unidentifiable. They all are located, stretching in an arc around the coastline from Dunadd in Kintyre and Dun Ollaig near Oban in the west, to Dun Foither (Dunnottar) near Stonehaven and Etin (Edinburgh) in the east. Also, in the east as far north as the southern side of the Moray Firth and in the southwest are to be found the traces of timber-laced or vitrified forts. Examples of these such are Craig Phadraig near Inverness, Burghead further east along the Moray Firth or and Dundurn further south in Strathearn. Some seventy of these strongholds are vitrified forts, where fire has at some time spread along the network of wooden beams fusing the rest of the dry-stone walling into a vitrified mass.Some of these hill-forts have been dated to almost the beginning of the first millennium 800 BC. Recent carbon dating of the wall at Burghead suggests it was built most likely about AD 400. The novel technique of driving iron nails more than seven inches long into the oaken cross beams found at Burghead links it to Dundurn. Abandoned in the ninth or tenth centuries or consumed in later medieval fortifications, the importance of these forts is easy to forget. But their period of occupation - for 500 years after the building of the wall (this is a specific wall—not before mentioned, and appears to be important for following conclusions) in the case of Burghead - compares well with the strength or viability of most of Scotland's medieval castles. They testify to the political strength of a warrior people otherwise almost unknown in written record.

In the west and north, the commonest forms of fortification were not like the hill forts or vitrified forts seen mostly in the Lowlands and the east. Rather, the forts were but the dun and broch, both stone-built structures of a modest size, dating from late in the first millennium BC. Over 500 broch sites have been identified along the Atlantic coast - the broch illustrated on the left is at Dun Carloway in Lewis in the Western Isles. These thick-walled and sometimes double-walled structures, often with towers between forty and fifty feet in height, which were built to defend a homestead rather than a natural promontory or the court of a king or chieftain, flourished in the first Century AD, the age of Agricola. They had a much shorter useful life than other forms of fortification. Their interpretation of these structures is the subject of fierce debate: for some archaeologists, the broch is as cherished an emblem of the distinctiveness or insularity of the culture it represents as are the images of Pictish art to some historians of the Picts. To some Irish historians, both the broch and the vitrified fort point to a common link with wider Celtic culture, not only in Ireland and but also elsewhere. The broch is a cousin of the Irish stone cashel or Iron Age stone forts in the northwest of Spain; and the timber-laced fort is to be found in pre-Roman Gaul.The point is they are unresolvable but are fundamental: all three kinds of fortifications stretch back well beyond before the point in 297 when a Roman historian attached the longest-surviving nickname, Picti (or 'painted people'), to one set of the native tribes in the British Isles. Brochs apart certainly, they suggest two points. First, Brochs had a long continuity in the material culture of the tribes who built and occupied them over a period of up to 1,600 years. And Second, they were also an essential, if loose, cultural unity amongst the various tribes first identified first by Ptolemy in the second century AD and later by other observers after him, who inhabited the bulk most of the mainland of modem-day Scotland north of the Forth-Clyde line. And Moreover, they hint, if darkly, at a common Celtic heritage which that underpinned these mysterious peoples.

Later, by about AD 600, more sophisticated forts, sometimes built on a hierarchical plan around an enclosure, such as Dunadd or and the inland fort at Dundurn at the head of Loch Earn in Perthshire, suggest the emergence by about AD 600 of viable over kings who could demand tribute from a loose grouping of tribes.

Click to go to the Next Page of this history : Early Peoples: The Roman historian Ptolemy named many small tribes in various parts of the country.Or return to Index of Scots History to 1400