Historic Scottish Battles

Rescue of Kinmont Willie (13 April 1596)

Source

This page is based on "A History of the Border Counties: Roxburgh, Selkirk, Peebles" by Sir George Douglas, 1899.Introduction

This was not a full battle, more a skirmish - but one that considerably enhanced the reputation of the Scottish Borders nobleman Sir Walter Scott of Buccleuch and threatened to cause Queen Elizabeth of England to decline to name King James VI of Scotland as her heir - and so alter the course of British history.Sir Walter Scott, 5th of Buccleuch, 1st Lord Scott of Buccleuch (1565 - 15 December 1611) was a Scottish nobleman and famous Border reiver (cattle rustler), known as the "Bold Buccleuch". Scott was the son of Sir Walter Scott, 4th of Buccleuch (himself grandson of Walter Scott of Branxholme and Buccleuch) and Margaret Douglas.

He married Mary Ker, daughter of Sir William Ker of Cessford and Janet Douglas, circa 1 October 1586,

Knighted by King James VI of Scotland in 1590, Buccleuch was then appointed in 1594 by King James VI as Keeper of Liddesdale and Warden of the West March (part of the Scottish Borders). It was in this capacity that two years later he effected the rescue of Kinmont Willie Armstrong from Carlisle castle, an exploit famous in Border lore that caused the name of Buccleuch to be popularly known all over Scotland and to be handed down to posterity as the 'Bold Buccleuch.'

Kinmont Willie and his Capture

Kinmont Willie was a redoubtable freebooter, whose proper name was Willie Armstrong. He is said to have been a descendant of the famous Johnnie Armstrong, who was hanged by King James the Fifth. Kinmont Willie was one of the most renowned of the Liddesdale reivers (cattle rustlers). He was a man of great personal strength, and had seven sons, all as brave and daring as himself, who in their time had committed many depredations on the English side of the Border. They had invaded Tyndale with three hundred followers, and had devastated a large tract of country, carrying off an immense booty; and naturally the capture and punishment of Kinmont Willie, and his accomplices was eagerly desired by the English Borderers.Kinmont Willie had attended a court held by the deputy Wardens at Dayholm, on Kershope, where a small stream divides the two countries. After the day's proceedings had come to an end, Kinmont and three or four friends were riding homewards, dreading no evil since it was a crime to be punished by death for either English or Scotsman to draw a weapon, even on his greatest foe, from the time of holding the court till next morning at sunrise; thus affording a sufficient interval for all to disperse and return home. It was necessary that this law should be rigidly enforced, otherwise the Warden Courts where sworn enemies were brought face to face, might become more potent in perpetuating strife, than securing the ends of justice.

But suddenly a force of two hundred English attacked Kinmont Willie and his companions. Resistance was out of the question, and the little party could only trust to the speed of their horses. Kinmont Willie was chased for several miles but at last was captured and taken a prisoner to Carlisle castle.

Diplomacy First

There is no doubt that the English had a heavy indictment against Kinmont Willie, and his capture and punishment had been anxiously sought by the whole population of the English Border area. Still, great offender as he was, the manner of his seizure was a flagrant breach of faith, and a gross violation of truce; aggravated by the fact that it was instigated or at least approved by Lord Scrope, the English Warden, into whose custody he was delivered.Buccleuch, the Scottish Warden, was bound to resent the outrage which was an insult to his country, and a defiance of his authority as Warden; he therefore wrote to Lord Scrope, and complained of the breach of truce, and demanded the release of the prisoner. Receiving no satisfactory reply, he swore that he would bring Kinmont Willie out of Carlisle castle with his own hand. Before, however, resorting to extreme measures, he resolved, like a well-known statesman of the present day, 'to exhaust the resources of civilization.' Accordingly he again wrote to Lord Scrope, and represented that his prisoner had been unlawfully captured, and was detained in direct violation of Border law. Scrope replied that Kinmont was such a serious offender that he could not release him without authority from the English Queen Elizabeth I.

Buccleuch then addressed the English Ambassador on the subject, and King James VI (pictured on the right) himself wrote to Lord Scrope and also to Queen Elizabeth, but without effect.

So Buccleuch thought it was time to take the matter into his own hands. He was a man of a proud temper and undaunted courage, and had the reputation of being one of the ablest military leaders in Scotland. To submit quietly to such insult was intolerable to his haughty nature, and he determined to vindicate his honour and the dignity of his office by taking Kinmont Willie out of Carlisle castle by force.

Rescue

Buccleuch took his measures carefully and secretly. Choosing a dark night, Buccleuch set out on his expedition, accompanied by a few of his chosen friends and retainers, among whom were Wat o' Harden, Scott of Goldilands, four of Kinmont's sons, and others to the number of about eighty.They assembled at the Tower of Morton (an Armstrong stronghold) in the Debateable Land, and within ten miles of Carlisle, all well armed and mounted, and provided with scaling ladders, sledge hammers, and all necessary implements. The rescue is splendidly described in the Ballad of Kinmont Willie, published in the 'Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border,' and which 'was preserved by tradition on the West Border, but much mangled by reciters, so that some conjectural emendations have been absolutely necessary to render it intelligible.' It is impossible to vouch for the antiquity of a composition received from oral tradition. Some form of the ballad may have been current shortly after the occurrence of the event to which it relates, but it may have undergone many changes in the course of transmission through two centuries. Scot of Satchells, whose history was published in 1688, dwells with great pride and pleasure on the gallant and daring rescue of Kinmont Willie, in which his father had taken part. He mentions various little incidents noticed in the ballad, and from this it had been supposed that he derived his information from it, but the inference may with equal probability be turned the reverse way, and the writer may have been indebted to Satchells for some of his facts. In all essential points the ballad agrees with the description given by Spottiswood and other historians.

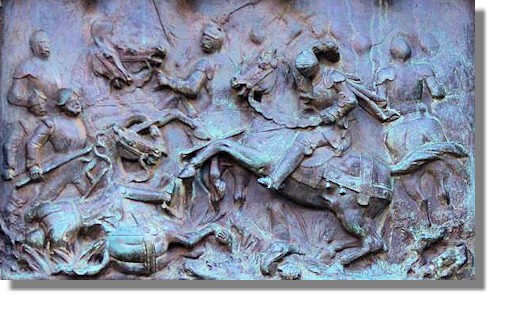

After describing all the preparations for their enterprise, and the dark tempestuous night, which was so favourable to their purpose, the poet describes their cautious advance to Carlisle Castle (pictured here). They had left their horses at some distance lest their neighing should give the alarm, and crept on knees, and held their breath, till they placed the ladders against the wall. Buccleuch himself was first over the wall, dealing with the night watchman. Once the raiding party was over the wall they made a lot of loud noise which made the garrison believe that must be a very large body of men taking over the castle.

Buccleuch's men, taking advantage of the confusion, plied their tools with such effect, that Kinmont Willie was soon released, and hoisted, still in leg irons on the shoulders of "Red Rowan", the starkest man in Teviotdale. As they passed under Lord Scrope's window, Kinmont roared out a lusty good night, and promised to pay him for his lodging the first time he crossed the Border. Having effected their purpose, the Scots retired as quickly as they had come. The garrison hardly recovered from their surprise, till the rescue had been effected, and the party re-crossed the river and were safe from pursuit.

Buccleuch had been careful to impress on his followers the necessity of doing nothing to give just cause of offence to the English Queen. He had vowed to take Kinmont Willie out of Carlisle Castle, without harming anyone. He adhered to this determination so strictly, that he ordered some prisoners, who had been released along with Kinmont, to be returned to Carlisle.

Reactions to the Rescue

.jpg)

When this daring rescue became known in Scotland, the people were loud in their praise, declaring that no such gallant exploit had been performed since the days of William Wallace.But when the news reached Queen Elizabeth I (pictured here), it aroused her extreme anger and resentment. To take a prisoner out of an English Castle was in her eyes a flagrant outrage and a national affront. She expressed her anger and demanded that the offender should be given up to her. It was represented to her that Buccleuch had only rescued a prisoner who had been captured and was detained in defiance of Border law; that in doing so he had harmed no single English subject, though he had had it in his power to take Lord Scrope prisoner, and to have sacked the whole town of Carlisle. Elizabeth, ignoring these facts, reiterated her demand that Sir Walter Scott be delivered up to her, to be dealt with at her pleasure. King James resisted this demand to the utmost of his power. Elizabeth insisted however, and it became necessary to bring the matter before the Scottish Privy Council. However, Buccleuch's adventure had many admirers, and there was a general feeling against yielding to Queen Elizabeth. Much correspondence ensued both between the crowned heads and their ministers and while this proceeded, fresh complications were added to it by the ever-recurring strife on the Borders.

About three months after the rescue of Kinmont Willie, Lord Scrope made a raid on the Scottish Border, involving atrocity unequalled even in that barbarous age. He led two thousand men into Liddesdale, and burned twenty-four houses, spoiled and carried away the whole goods and gear within four miles of the Border, apprehended the men and chained them two and two in a leash like dogs.

To avenge this raid, Sir Walter Scott and Sir Robert Ker of Cessford, made an inroad on the English Border and harried the country on all sides with fire and sword, carrying off thirty-six prisoners, whom he afterwards put to death. Other marauding expeditions by both sides followed, the hostility being kept up with unabated fury, and it would be hard to say which side was most to blame.

Queen Elizabeth I demanded that Buccleuch should be delivered into her hands, and among other means of forcing King James to yield to her wishes, she threatened to stop the payment of an annuity which he received in respect of certain lands belonging to him in England. (The Royal exchequer was not in a flourishing condition, and this would seriously inconvenience James). The majority of his counsellors were of opinion that it would be less dishonour to the King and his kingdom were he to be driven from his throne, than to be thus forced to disgrace himself for money. He could not now deliver up Buccleuch, since it would be reported that he had done so by force and for gain. The position of matters was very embarrassing to James. He was by no means anxious to give up Buccleuch who had done nothing unbecoming a loyal Scotsman; but Elizabeth insisted so strenuously, that it seemed as if the dispute must end in war (which would have made it impossible to inherit the English throne which he had a strong claim on due to blood line).

So King James was eventually forced to yield to the urgency of Queen Elizabeth's demands, and Sir Robert Ker and Sir Walter Scott accordingly yielded themselves to the English at Berwick. But the fame of his gallant exploit meant that when he entered England he was treated more like a distinguished guest than a captive brought to answer for his offences against the government. He also made a very favourable impression on the Queen, for though she had insisted that Buccleuch should yield himself as her prisoner, when this was conceded she was mollified and treated him with marked kindness, appearing to have forgotten that he had been a most implacable enemy. Buccleuch enjoyed great popularity during his stay in London, and was sumptuously entertained by the best society according to later historical writers.

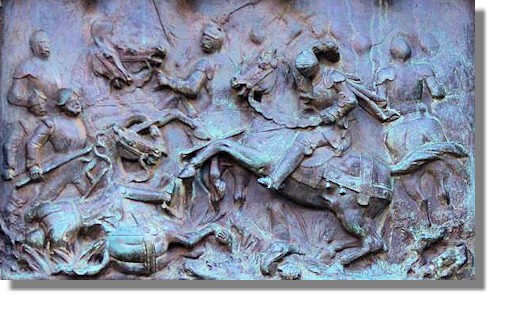

It is reported that Queen Elizabeth asked Buccleuch how he dared undertake an enterprise so daring and so presumptuous, when he answered, 'Madame, what is there that a brave man dare not do?' This reply was so much after the Queen's own heart that she turned to the bystanders and said, 'with ten thousand such men, our brother of Scotland might shake any throne in Europe.' (The graphic on the right is from a bronze relief in Edinburgh illustrating Buccleuch's audience with Queen Elizabeth I)Buccleuch remained a year in London in honourable captivity, and afterwards visited France, where he stayed another year.

On the accession of King James VI to the English throne, Buccleuch distinguished himself in reducing the Border strife, holding the office of Keeper of Liddesdale. He was created 1st Lord Scott of Buccleuch and was invested as a Privy Counsellor in Scotland. His son, also Walter Scott, became 1st Earl of Buccleuch and in the following centuries Buccleuch the largest private landowner in the UK.

Where else would you like to go in Scotland?