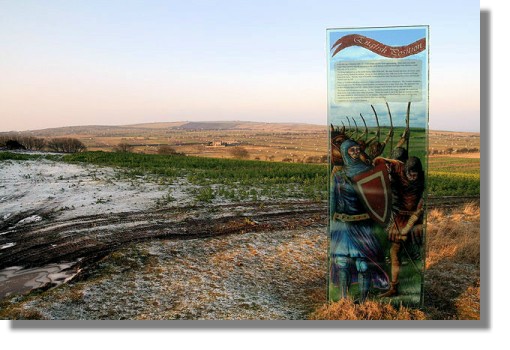

Halidon Hill Battle Site © Lisa Jarvis via Wikimedia Commons

Introduction

In the early part of the 14th century the fragile and volatile relationship between England and Scotland was placed on a more even keel with the Treaty of Northampton in 1328. As part of the Treaty the young son of King Robert I of Scotland was married to the sister of King Edward III of England, and Scotland was assured political autonomy. The following year Robert died leaving his son and heir only five years old. The young boy was crowned King David II at Scone in 1331. But Edward Balliol, son of the former King John, continued to press his claim to the Scottish throne, and in 1333 he persuaded Edward III with promises of land, should he succeed, to take a direct involvement in his cause. Edward now openly supported Balliol and in the spring of 1333 headed north to lay siege to Berwick, the Scottish-held town that was the prize concession promised by Balliol. Over the course of only 400 years, Berwick changed hands more than a dozen times.

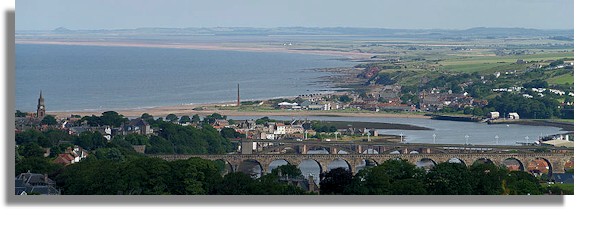

A Scottish force under the Regent Sir Archibald Douglas attempted, and failed, to draw Edward away from Berwick. With the town now surrounded the defenders sued for a truce. The terms eventually agreed were that Edward would accept the town relieved only if a Scottish force relieved the town, under certain conditions. Otherwise, Berwick would surrender to Edward. On hearing of this agreement Douglas hurried to the relief of the town. (Graphic showing Berwick on Tweed from Halidon Hill © mattbuck via Wikimedia Commons Arriving on the 19th July, Douglas approached from the north. On leading his troops to the summit of the hill called Witches Knowe he saw the English army drawn up before him to the south, on the slopes of Halidon Hill.

The Battle

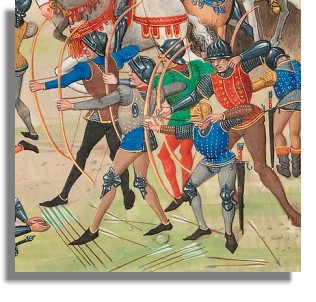

Edward's army was some 8,000 strong and only a small force had been left to guard Berwick. Douglas had by far the larger force with some 14,000 troops. Part of the Berwick agreement had stipulated that the Scottish force had to take battle to the English. Edward had chosen his ground well and deployed his troops on the northern slopes of Halidon Hill with a wide area of marsh to the fore and blocking the routes into the town. Douglas had to advance down Witches Knowe and across an area of marshland in front of the English positions before he could engage. (Graphic from plaque at Halidon Hill © Lisa Jarvis via Wikimedia Commons

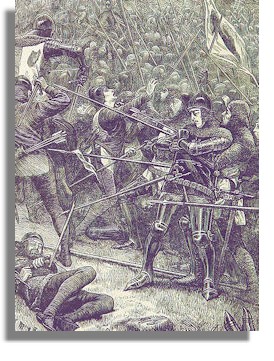

The Scots did not attack at once. Douglas waited until midday when the tidal River Tweed was at its full height in the hope of pushing back the English troops into its waters. Edward used this time to rally his troops who were somewhat disturbed by the Scottish weight of numbers. The Scottish knights and men-at-arms had dismounted for the battle, perhaps due to the nature of the terrain or perhaps to match the tactics of the English whose knights and men-at-arms had also dismounted. As the Scots advanced across the bog, the English archers opened fire. Those in the centre and on the right of the Scottish line, unprotected from the hail of arrows, were quickly dispelled. On the left of the line, nearest the sea, Douglas led the attack and here the fighting was much fiercer. But fierce though the fighting was it was still over quickly with the Scottish forces breaking and attempting to flee. For many of the heavily armoured and dismounted knights the flight from the field was hampered not only by the bog but by their own grooms who, witnessing the defeat in the valley below them, turned and fled with the horses. On seeing this, the English mounted and pursued them for some seven leagues. The Scots were routed, Douglas killed and Berwick surrendered.

Michael and Andrew Scott

Sir Michael Scott took over as the second Laird of Buccleuch. Michael's reign was starting to see a bit more violence and being a staunch supporter of Robert the Bruce, and later of his son King David II, took an active part in the battle and distinguished himself during the Wars of Scottish Independence. Michael was to finally meet his maker at the Battle of Neville's Cross at Durham in 1346.Sir Andrew Scott, of Balwearie, also distinguished himself by his patriotism, and was later slain at the taking of Berwick by the Scotts in 1355.

Defeat

Halidon Hill had been a disastrous defeat for the Scots which saw Lord Douglas with 14,000 men get mauled by the English archers. The fields were strewn with Scots bodies for 5 miles around, comprising Douglas himself, six Earls, seventy Barons, five hundred knights and 4,000 men.Following the English victory at Halidon Hill the town of Berwick and the lands of the Borders and Lothian were ceded to England by Balliol. This ensured that warfare between the two countries would continue as the Scots fought to regain their lands. For Edward III his first battle was an important lesson in tactics, a lesson he was to employ to great effect against the French at Crécy and Poitiers.

The battlefield area is now fully enclosed but remains agricultural with only a few scattered farms. The marshy ground between the two hills has been drained. Access is possible along Grand Loaning Lane which runs across the centre of the battlefield and via a circular conservation walk which goes around Halidon Hill taking in the English positions.

If you want to read more on the Battle of Halidon Hill, Sir Walter Scott wrote a book on the battle which is now freely available on the Web at Halidon Hill: A Dramatic Sketch from Scottish History. It is written in his inimitable style, describing the events in great detail.

Viewpoint on Halidon Hill © Rod Allday via Wikimedia Commons